Most of these reviews ran in the Kitchener-Waterloo Record and Guelph Mercury; two of them ran in the winter issue of Magnet. More tomorrow, but in alphabetical order here, they are: Baby Dee, Erykah Badu, Black Mountain, Burning Hell, Cadence Weapon, Cat Power, Devastations, Fairmont, Forest City Lovers.

Baby Dee - Safe Inside the Day (Drag City)

Life is a cabaret, old chum. Especially if you’re a hermaphrodite harpist in a bee costume who plays accordion on a giant tricycle in a circus, while acting as musical director of a Catholic church by night. Or if you end up back in your hometown of Cleveland working for a tree removal service, while touring Europe with David Tibet’s Current 93 in your spare time.

This kind of life story explains a lot about Baby Dee, whose music immediately conjures up stereotypes of Warholian drag cabaret in 70s New York City. Unlike her friend Antony, Dee’s androgynous voice isn’t angelic—it’s ridiculously melodramatic, especially when she writes herself bewildering choruses with the refrain: “Spill the milk/ steal the meat/ life is bitter and death is sweet/ all the bacon that a boy can eat.” Breakfast pops up as a bizarre life metaphor again when she laments how “father, son and holy ghost/ stole the bacon and burnt the toast.”

Baby Dee is certainly not without talent, especially as a keyboardist; the two instrumentals here are lovely. However, on the high camp of “Big Titty Bee Girl (From Dino Town)” Dee’s vocals sound straight out of community theatre, instead of the restraint and guidance you might expect from co-producer Will Oldham. Baby Dee is an intriguing figure for a variety of reasons, but as the album progresses, one of her titles sticks in the mind: “The Dance of Diminishing Possibilities.” (Magnet, Winter 2008)

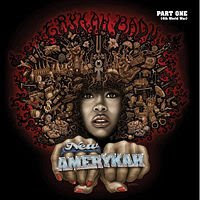

Erykah Badu – New Amerykah Part One (4th World War) (Universal)

Erykah Badu – New Amerykah Part One (4th World War) (Universal)The last time Erykah Badu wrote an album, George W. Bush was not yet the leader of the free world. Eight years later, her vision of New Amerykah is a druggy, discombobulated moral morass on the verge of societal collapse. To her credit, these vivid nightmares are translated into a brilliant music vision.

Badu draws from the deep well of Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield here, along with other 70s soul pioneers who had seen the dream of civil rights erode under the weight of economic collapse, political apathy and an influx of hard drugs into the community. Consequently, their brand of soul music started painting with abstract colours borrowed from Miles Davis, rather than the punchy rhythms and horn shots that accompanied earlier messages of affirmation.

Similarly, New Amerykah refuses to settle for easy answers, musically or lyrically. Badu spends much of her energy in an inquisitive mode (“What if there were no niggers, just master teachers?”), while the heavy hip-hop grooves beneath her rattle foundations. Badu rounds up an astounding arsenal of producers: ?uestlove of the Roots, Sa-Ra Creative Partners, jazz vibraphonist Roy Ayers, and 9th Wonder.

The two songs featuring Madlib are the trippiest: "The Healer," with its wobbly descending bass line and a clipped cymbal crash that sounds like a burst of white noise; and "My Children," which consists of little more than a monstrous hip-hop beat, African drums and a vocal chant, each element slipping in and out of the beat while Badu sings, “Hold on, my people.”

This isn’t the easy listening hip-hop jazz of Badu’s breakthrough debut album, nor is it the swaggering soul sister of 2000’s Mama’s Gun. Instead, Badu has reinvented herself entirely to address the musical and social climate she awoke to in 2007, and has made a dense, difficult and fascinating soul classic that sounds like nothing else in modern R&B or pop.

And the good news is that, rather than sometime in the next decade, Part Two is expected no later than this summer. (K-W Record, March 20)

Black Mountain – Into the Future (Scratch)

Black Mountain – Into the Future (Scratch)The album title is more than a bit ironic, for Black Mountain’s harshest critics have always argued that there’s a fine line between homage and retro necrophilia. But on their 2005 self-titled album, Vancouver’s sultans of stoner sludge came out swinging with a slab of 70s psychedelic garage rock that pushed all the right buttons, even if it was all too easy to play spot-the-influence.

This time out there are plenty of welcome changes to the band, starting with an increased role for spellbinding vocalist Amber Webb and keyboardist Jeremy Schmidt, both of whom ratchet up the spook factor in some of the ghostlier grooves. Yet singer/songwriter Stephen McBean appears to have dropped the ball entirely, giving his band little more than threadbare sketches to work with. His talented comrades—each of whom has a worthwhile side project when not touring the world with Black Mountain—don’t sound committed to the task, especially powerhouse drummer and longtime McBean collaborator Josh Wells, who approaches most of these songs with little more than a shrug.

At their finest, Black Mountain still outshine most of their peers in this admittedly limited genre, but the Future here is full of little more than wasted opportunities. (K-W Record, January 25)

The Burning Hell – Happy Birthday (Weewerk/Outside)

The Burning Hell – Happy Birthday (Weewerk/Outside) On the portrait found inside this CD, Peterborough singer/songwriter Mathias Kom is pictured against a bleak, wintry Ontario backdrop in a dapper grey suit, clutching a ukulele case in one hand while he’s being pulled to the heavens by a cluster of bright blood-red balloons, Mary Poppins-style. From the slightly bemused look on his face, this happens to him all the time and it’s getting a bit tiresome.

There’s nothing tiresome about The Burning Hell itself; Happy Birthday is a fully-realized debut album, a perfect balance of mirth and the morbid. Like the Magnetic Fields’ Stephin Merritt, Kom wields a deep baritone and a ukulele and drops tiny, dry and wry punchlines into his songs. And yet underneath the deadpan demeanour are heartbreaking Leonard Cohen-esque songs paying tribute to classic rock dinosaurs and detailing the misadventure of vengeful ghosts, set to aching accordion and mournful cellos played by some former members of The Silver Hearts. Along with his knack for last-call singalongs, Kom also shows off a skill for writing duets—the most gorgeous of which is "Municipal Monarchs," featuring Guelph’s Jenny Mitchell of the Barmitzvah Brothers (now a new addition to the band).

Every song here announces Kom as one of the finest new songwriters in Canada—though don't take my word for it. As Kom himself will tell you on one of the more uplifting tracks here, "Everything You Believe Is A Lie." (K-W Record, January 18)

Cadence Weapon – Afterparty Babies (Upper Class/EMI)

Cadence Weapon – Afterparty Babies (Upper Class/EMI)Canadian hip-hop is much like Canadian film—we do better with the weirdoes than with the commercial windfalls. Which, along with his current tourmate Buck 65, is why Edmonton's Cadence Weapon is likely to be the first Canadian hip-hop artist to make a significant international impression since the Dream Warriors (who themselves were decidedly against the grain during their heyday).

Mr. Weapon—also known as Rollie Pemberton—already keeps good company. This, his second album and the follow-up to the Polaris-nominated Breaking Kayfabe, is being released in the US on the same label as Tom Waits; it's coming out in the UK on the progressive 21st century hip-hop label Big Dada; here at home he tours with Final Fantasy.

That kind of introduction gives you an idea of the wealth of influences at work here. Afterparty Babies opens with an a capella doo-wop track titled "Do I Miss My Friends?", which seems apt for an artist who flourishes in the cracks between musical communities. Tellingly, that track is the only nod here to traditions of any kind, either inside or outside hip-hop orthodoxy. From there on in, Cadence Weapon charts his own path.

Afterparty Babies is a rollicking ride through the most inventive strains of late 80s hip-hop (Bomb Squad, De La Soul), neo-electro dance party beats not unlike his neighbours in Shout Out Out Out Out, some tricky turntablism from his longtime accomplice DJ Weasel, abrasive distorted rhythms and playfully glitchy sampling.

Those catholic interests are reflected in his often-arcane list of lyrical references, which include Trudeau's ascot, Aphex Twin, Friendster, James Frey, Ryerson coke dealers, The Globe and Mail, and the perils of wearing pink without irony.

And of course, only a self-deprecating Canadian hip-hopper would write a song called "Unsuccessful Club Nights." Only unlike his debut album, this time out Cadence Weapon drops his tendency for density often enough to make some of these tracks actually suitable for dancing, not just the headier soundscapes heard on his debut.

It's this dexterity that makes Cadence Weapon the great hope of Canadian hip-hop: as a lyricist, as a producer and, as is so rare in this country or in hip-hop itself, as an iconoclast with a taste for the visceral who hits you in the gut instead of stuck there stroking your chin. (K-W Record, March 13)

Cat Power – Jukebox (Matador)

For an established singer/songwriter, covering other people’s songs is more often than not a cop-out—especially when you cut a whole album of them and it turns out to be your breakthrough hit. That’s what happened to Cat Power—aka Chan Marshall—with 2000’s The Covers Record; though it was undeniably superior to anything her nascent talent had released up to that point, it was the way she crawled deep inside and recontextualized songs by Lou Reed, the Rolling Stones and Nina Simone that made it much more than a cheap career move.

Now that Marshall is a pseudo-mainstream indie celebrity—and occasional fashion model—and has earned enough credibility for her own songs that she doesn’t really need to revisit the covers concept. And yet here we have Jukebox, where she tackles iconic songs like "New York New York," Hank Williams’ "Rambling Man" and Joni Mitchell’s "Blue," only to render the chords unrecognizable and the melodies considerably more minor-key, breathing entirely new lives into the lyrics as a result.

To call it her finest album to date isn’t a backhanded compliment: none of these performances attempt to piggyback on our familiarity with the original versions. And this being Marshall’s first post-rehab record, her smoky, sultry voice appears here in full focus, as opposed to the slightly catatonic state heard on 2006’s The Greatest.

That album was recorded in Memphis with vintage soul musicians—and yet the end result was more Sarah McLachlan than Stax Records. Some of those veterans return to greater effect here, including classic soul songwriter Spooner Oldham, and Marshall herself lays off the piano and guitar to concentrate on her vocals.

The song selection frequently draws from music fandom itself: from Bob Dylan’s "I Believe In You," George Jackson’s "Aretha Sing One For Me," Mitchell’s "Blue" and Marshall’s own "Song to Bobby." By immersing herself in the work of others, Marshall once again takes a quantum leap into discovering the best sides of her own talent—which bodes very well for her next batch of original songs. (K-W Record, January 25)

Devastations – Yes, U (Beggars Banquet)

Devastations – Yes, U (Beggars Banquet)Devastations have the simmering suave nature of Bryan Ferry, the dark and stormy rock atmospherics of Interpol and a dash of Nick Cave, all of which guarantees them a soundtrack spot in some film where it’s always raining and the hero takes late night drives in search of either redemption or revenge. Devastations are experts at conveying mood, which might have something to do with growing up in isolated, expansive Australia and resettling in the European centre of Berlin.

They get full points for production value and the fact that they occasionally catch glimpses of sunlight amidst the gloom and doom, but the songs themselves are plodding and threadbare, the lyrics inconsequential. One of the better tracks here, "Avalanche of Stars," borrows a keyboard riff from Nancy Sinatra’s "You Only Live Twice"; while the aquatic bass, ancient drum machine and pedal steel provide a glorious backdrop, the whole piece still feels like it’s waiting for someone else to bring it all into a tighter focus.

There’s a great backing band here for someone else’s project; on their own, Devastations should farm themselves out for soundtrack work. (K-W Record, February 21)

Fairmont – Coloured in Memory

Fairmont – Coloured in Memory(Border Community/Fusion III)

Many electronic artists who have built their reputation on techno singles end up choking on a full-length album, especially when they decide to step off the dance floor and lose the pulsating beat to explore different avenues. Toronto expatriate Jacob Fairley, on the other hand, has no qualms about losing his beat crutches and embarking on Tangerine Dream-like voyages into shady cinematic territories, or picking up an electric guitar and whispering into the microphone.

Fairley resides in Berlin these days, but it’s not hard to guess that from Fairmont: the synths sound like vintage 70s gear, the beats are derived from the minimalist clicks’n’cuts movement of the early century, and there are subtle shades of warmth underneath the icy electro exterior, much like the reigning queen of Berlin, Ellen Allien, does in her own work. The glam rock guitars that invaded Fairley’s last release are nowhere to be found; at a time when so many of his contemporaries are branching out into more organic or rockist sounds, Fairley is quite content to make an entirely synthetic record.

But the aesthetic alone doesn’t make this one of the finest Canadian electronic albums in recent memory. His own vocals are barely noticeable and, as to be expected, the beat-friendly tracks rely on repetition and evolution. Yet he still has a songwriter’s ear for melodic hooks and arrangements and knows how to sequence an album: Coloured in Memory never stays in one mood for very long, and the ambient tracks are just as compelling as the beats he’d likely play out for a crowd in a DJ set—which makes it sound just as good on Sunday morning as it does on Saturday night. (K-W Record, March 6)

Forest City Lovers – Haunting Moon Sinking (Out of This Spark/Sonic Unyon)

Forest City Lovers – Haunting Moon Sinking (Out of This Spark/Sonic Unyon) Beauty lies in the rows of red brick houses in the morning dawn. New possibilities arise every time the streetlights come to life. The small town girl in the big city maintains her poise amidst the bustle, taking carefully detailed notes on her new surroundings and setting it all to lovely melodies that dare to dream beyond all the other bedroom singer/songwriters in her neighbourhood.

On the one hand, singer/songwriter Kat Burns is one in a long line of similar southern Ontario artists with a mastery of minor key melancholy and string-laden songs about leaving those small towns behind. But she’s more multi-dimensional than most, with a band of Lovers who rock out when they have to, are able to step into vintage cabaret mode without a hint of clumsiness, and do a classy dance around Burns’s subtle melodies.

Considerable help comes from bassist Kyle Donnelly (also of labelmates the D’Urbervilles) and violinist Mika Posen. Though Burns often performs solo, this material comes alive in this duo's dynamic hands; even when drummer Paul Weadick backs off, Posen and Donnelly drive the songs away from the more sedate territory of earlier material.

Together with the D’Urbervilles’ debut album and last year’s scene-defining compilation Friends in Bellwoods, Haunting Moon Sinking marks a formidable debut for the new label Out of This Spark. If they keep up this level of quality, they’ll have the best label roster in Canadian indie rock. (K-W Record, March 13)